BLITZ KRIEG PUBLISHING

Should You Teach

Your Children About Diversity?

as published in Metro Parent Magazine

By Donna

Gundle-Krieg

Does fostering an

appreciation of diversity matter to you and your family? Or do you roll your

eyes when you hear what some call "the D word"?

As a parent, do you believe you should actively teach your children about diversity? Or do you feel you should let integration happen naturally, assuming people will mix to a healthy degree?

Parents across the

metropolitan Detroit area are definitely divided on these matters. Denise

Derocher of Milford, a mother of two daughters in middle-school, had a

negative reaction to the word "diversity."

"I believe that if a

person learns to look at others and love them for what they are on the

inside, and not for what they look like, they will not need any diversity

training," she said. "Diversity training is like a band-aid for not learning

to love."

But Shirley Stancato, president of New Detroit, a coalition of leaders dedicated to improving race relations, disagreed.

"To tell me you are

color-blind is an insult. You are not acknowledging me (as an African

American) if you are not seeing color," she said. "If we donıt embrace and

understand other othersı cultures, then we become extinct."

Mary Burck of

Farmington Hills, an artist and mother of a son in middle school, also

believes that diversity training matters. "I was raised in an all-white town

in the upper peninsula," she said. "We were always starved for cultural

experiences. As a result, I feel thereıs racism and insensitivity up there

because most people haven't ever been exposed to diversity."

Burck argues that

the earlier you expose children to different cultures, the better. "You have

to make it a positive experience and reinforce how much people are the

same," she said.

Indeed, "We are

more alike then unalike," writes Maya Angelou, renowned poet and national

spokesperson for the National Conference for Community and Justice (NCCJ).

The NCCJ provides diversity training and experiences to businesses, churches

and schools, including about 50 schools in the metropolitan Detroit area.

Daniel Krichbaum,

NCCJ-Detroit's executive director, expanded on Angelouıs quote.

"Regardless of our similarities, in order to understand and respect our

uniqueness, we need to know what makes us different," he said. "It is our

differences that make us unique and give us value."

Krichbaum added that

this knowledge must be a two-way street. "For example," he pointed out, "we

have stereotypes and prejudgments against Yoopers from the upper peninsula,

too."

Deanne Orlando, a Livonia elementary school teacher and mother of four teens, believes that even if we live in homogenous communities, we're staring at diversity every day.

"Is my classroom

diverse because itıs a pleasant mix of cultures, or because I have

cognitively impaired kids, gifted kids and resource room kids all in the

same class?" she wondered.

And what about

different religions?

Stancato agreed with

Orlando that people are diverse in many ways. "However, race is the toughest

issue to deal with," she insisted. "The metropolitan Detroit area continues

to be the most segregated area in the nation in terms of race, and this is

costing us in many ways."

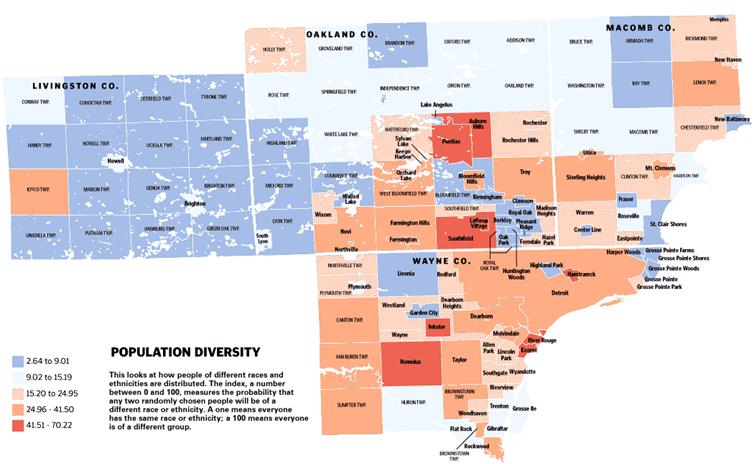

Why are we segregated?

Demographic trends show that minority population growth and white

flight is expanding in a ring pattern away from Detroit. Stancato maintains

that this ring is caused because "white people flee from other cultures,

which creates segregation."

Doug Wilson of

Oxford believes that segregation often exists simply because people

naturally drift toward those who are like them. "People often find homes

where they believe they will fit in, as well as, what they can afford," he

said.

James Jones a

Pontiac factory worker and father of five agreed. "Iıd love to move my black

family into a multi-cultural neighborhood, but I simply canıt afford it."

Kim Small of

Highland, a mother of three teens puts a different spin on the issue.

"Shared immigration experience, culture and language cause people to huddle

together," she said. "This is not at all a negative experience. A

non-diverse group helps give a family a support system. As many people are

pulled away from extended family for employment reasons, the attachment to

homogeneous groups is support for what was lost."

Small added that

those of similar backgrounds have always been drawn together for positive

support systems, and notes that this initial assimilation was seen with the

Poles in Hamtramck, the blacks in Paradise Valley, the Germans in

Frankenmuth, and the Dutch in the city of Holland.

Burck agreed that we tend to huddle together, and so has tried to get her son to invite people of other backgrounds over to play. "However, it seems like he always gravitates back to being friends with those who are the same Caucasian race he is," she said. "People just seem to be more comfortable being

with others who look

and act like them."

However, she said

she still believes "we need to get out of our comfort zones and stretch

ourselves enough to have conversations and find common ground with people of

other races. Sometimes schools, neighborhoods or workplaces may be plenty

diverse, but each cultural group sticks to their own."

As Krichbaum sees

it, "Inclusion is as important as diversity itself. This means there is the

sense that everyone has equal value, equal opportunity and equal say

regardless of their background." The NCCJ defines an inclusive school

culture as "one that works to affirm, not just tolerate, differences."

Stancato added that

to be inclusive, "We need to have race conversations. But people donıt want

to talk about race issues. You must have the tough conversations to move

on."

Language barriers

Burck suggested the biggest barrier to having these tough conversations

is the fact that different races and cultures don't speak English very well.

"I don't speak a second language, so itıs awkward to start a conversation

with someone from another country," she said.

The number of

Michigan residents who speak a language other than English at home

increased by nearly 40 percent over the past decade, according to the

U.S. Census Bureau. The languages most commonly spoken in Michigan, other

than English, are Spanish, Arabic and German. Of 9.3 million Michiganians

age 5 and older, 8.5 million speak only English.

Should we be

learning other languages and teaching them to our children? Or should we

simply insist that immigrants learn our language? Groups such as U.S.

English, which advocates making English the official U.S. language, say

outreach efforts should be curtailed. The organization believes that unless

we're going to put things out in 300 languages, we should put our money and

efforts towards teaching people English.

But postal worker

Jon Benk of Detroit, a father of two young adults disagreed. "I think it's

increasingly important for people to understand the language of the global

community," he said. "We must know other cultures and be able to speak their

languages."

History and geography lessons

In addition to teaching more about languages in our elementary schools,

should we also teach our students more about the diversity of races and

religions? Or should this be taught in the home? Can parents assume that the

schools and the culture outside their homes will do it?

"If you value

diversity, you will teach it," said Stancato. "Parents donıt let others

teach their children the basics of living, so why should they let others

teach their children about diversity? It absolutely has to go on in the

home."

Wilson of Oxford

agreed. "Diversity can be learned outside the home, but it takes an awfully

insightful individual to form values different from the ones he was raised

with," he said. "Accepting others comes more naturally to kids because they

have no previously aligned judgment."

Pauline Saroki, a

public defender in Detroit of Chaldean origin, had these thoughts, "Those

who live in all-white suburbs and raise their kids to believe that people

who are not like them are not worthy of their consideration, make me sad.

Perhaps itıs not too late for their children. Unfortunately, these parents

arenıt going to be the messengers."

Bonnie Lynch of

Milford, a mother of two young children had a different opinion. She lived

in diverse areas while growing up, and worked in Detroit her entire career.

"Iım totally against teaching diversity to anyone, especially in our

schools," she said. "Instead, letıs teach how weıre all Godıs children and

that inside we are all alike! Let's celebrate what we have in

common."

But if parents donıt

address diversity issues, can tolerance and understanding be gleaned from

outside sources?

Krichbaum said there

are many influences that determine how tolerant a person will be. "The NCCJ

and other groups such as New Detroit have programs to help teach these

values. The media also plays a big part. But just watching other cultures on

television is not enough. People learn best face-to-face," he said.

Denise Gundle-White,

a Farmington Hills teacher, agreed that face-to-face contact is the best way

to get people connected, and says that sharing experiences and relationships

with those who are different from ourselves is the best way to learn

diversity.

"The mere

opportunity my students have to know various other students is such a gift,"

she said. "Diversity is much more valuable when it just happens, rather than

the typical idea of 'teaching' diversity lessons to a homogenous group."

Seek out cultural experiences

If sharing experiences is the key to learning about differences, how can

parents teach their children about diversity if they live in a segregated

town and go to segregated schools? Benk suggested that people "go to events

and festivals to learn othersı cultures. "The metropolitan area is full of

such festivals where you can learn about the food and music," she said.

Stancato added that

there are certain metro-Detroit destinations that are very diverse. "When I

go to the Detroit Zoo and see the mix of people there, I think this is how

it should be everywhere.ı" she said. She recommends parents bring their

children to places that celebrate culture, such as the Detroit Institute of

Arts and the Museum of African American History.

Krichbaum agreed. "There is more to education than academics," he said. "We must teach our children about the world."

He believes that

students who attend schools with one ethnic group are disadvantaged when

going on to college and the workplace. "While there has been progress in

workplace diversity, most of our neighborhoods and schools are still not

diverse," he said.

Diversity in business

Krichbaum went on to point out that, "companies are attracted to

communities where cultures can assimilate and people can get along. To

increase business growth in this area, Michigan should be attractive to

those from across the world. There are reasons businesses and people choose

communities such as Farmington and Ann Arbor. These towns are considered

desirable places to live because of their rich cultural diversity."

Stancato said that the lack of diversity and inclusion in most neighborhoods

has caused a Michigan Brain Drain. "We're losing young people at an alarming

rate," she said. "One reason is segregation. Young people want diverse

communities."

Wilson noted that in metro Detroit, the younger crowd definitely has a leg up on the older crowd in regard to diversity.

"As borders break

down in our already well-developed push to globalize, diversity has taught

many large international players of its importance in lost profits and

mistakes," he said. "In business, itıs a dog-eat-dog world. If youıre not

culturally sensitive, it can hurt you in too many ways to count."

Even in non-business jobs, diversity matters. Explained Saroki, "I am an American born Chaldean who has the privilege of living a very diverse life. My job as public defender gives me the opportunity to empathize with others of different cultures. It also requires that I do so."

Other costs of

segregation

Krichbaum

believes that in addition to impacting business and jobs, diversity impacts

our region in other important ways, too.

"The

further out we build, the more expensive it becomes, which creates a host of

social infrastructure needs," he said. "If we spread out urban culture, we

lose our urban core." He cited sprawl problems such as higher taxes to

afford new schools, roads, businesses and communities.

Stancato agreed.

"The cost of segregation is that people pay," she said. "They pay more

economically for houses, taxes and transportation, in addition to

sacrificing the diversity experience."

Those who live in

segregated areas are not always happy about it. Milford's Derocher does not

live in a multi-cultural area, and wishes her area had a greater variety of

races. "I hope and pray that some day our world will look a lot more

integrated," she said. "Until then, I think the best response is to teach

love, not diversity."

Farmington's Burck

concluded, "the fact that many of us live in a segregated community is not

really bad, just sad. People who choose to live somewhere because that place

is all one race seem like they are missing out on one of the greatest joys

of living."

Donna Gundle-Krieg

of Milford a freelance writer and mother of two, recently wrote and

published From Desert to Detroit, a childrenıs book about an Iraqi

family who moves to Detroit to face many big city problems, including

prejudice after 911.

"I wrote the book to

help educate older children and others on some of the complex international

issues we face today," she said. "Readers are drawn into the world of this

family from another culture, and hopefully gain a better idea what itıs like

to be in their shoes."

For more information, visit www.blitzkriegpublishing.com

Tables below are listed separately under blitzkriegpublishing.com/diversitytables

|

Geographic Area |

2000 Census one race only |

||||

|

Non- Hispanic |

Hispanic |

||||

|

White |

Black or African American |

American Ind. and Alaskan Native |

Asian |

||

|

Livingston County |

97.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

|

Macomb County |

93.5 |

2.7 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

|

Oakland County |

83.5 |

10.1 |

0.2 |

4.0 |

2.2 |

|

Wayne County |

53.0 |

41.6 |

0.3 |

1.6 |

3.5 |

|

Geographic Area |

2000 Census once race only |

||||

|

Non- Hispanic |

Hispanic |

||||

|

White |

Black or African American |

American Ind. and Alaskan Native |

Asian |

||

|

|

|||||

|

LIVINGSTON COUNTY |

|||||

|

Livingston County ALL |

97.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.6 |

1.2 |

|

Brighton city |

95.7 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

|

Brighton township |

96.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

|

Cohoctah township |

97.2 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

|

Conway township |

95.2 |

0.3 |

1.4 |

0.1 |

1.3 |

|

Deerfield township |

97.2 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

|

Genoa township |

96.6 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.0 |

|

Green Oak township |

95.0 |

1.6 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

1.3 |

|

Hamburg township |

96.5 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

1.1 |

|

Handy township |

96.2 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

1.1 |

|

Hartland township |

97.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

1.1 |

|

Howell city |

94.7 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

1.4 |

2.2 |

|

Howell township |

97.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

|

Iosco township |

94.2 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

3.7 |

|

Marion township |

97.0 |

0.0 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

|

Oceola township |

96.4 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

1.1 |

|

Putnam township |

97.2 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.9 |

|

Tyrone township |

97.1 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

|

MACOMB COUNTY |

|||||

|

Macomb County: ALL |

93.5 |

2.7 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

1.5 |

|

Armada township |

97.1 |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

1.5 |

|

Bruce township |

94.6 |

1.8 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

1.8 |

|

Center Line city |

92.8 |

3.0 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

1.5 |

|

Chesterfield township |

92.0 |

2.9 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

2.5 |

|

Clinton township |

90.0 |

4.6 |

0.2 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

|

Eastpointe city |

91.2 |

4.7 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

|

Fraser city |

95.6 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

1.3 |

|

Harrison township |

93.6 |

2.4 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

1.5 |

|

Lake township |

88.8 |

1.3 |

2.5 |

7.5 |

0.0 |

|

Lenox township |

77.4 |

16.4 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

2.8 |

|

Macomb township |

95.0 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

1.4 |

1.5 |

|

Memphis city |

97.5 |

0.1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

|

Mount Clemens city |

74.5 |

19.5 |

0.7 |

0.5 |

2.3 |

|

New Baltimore city |

96.0 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

1.3 |

|

Ray township |

97.0 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

1.2 |

|

Richmond city |

92.7 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

4.7 |

|

Richmond township |

96.3 |

1.0 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

|

Roseville city |

92.4 |

2.6 |

0.4 |

1.7 |

1.5 |

|

St. Clair Shores city |

96.0 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

|

Shelby charter township |

93.8 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

2.1 |

1.7 |

|

Sterling Heights city |

89.8 |

1.3 |

0.2 |

4.9 |

1.3 |

|

Utica city |

92.5 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

2.6 |

2.1 |

|

Warren city |

90.4 |

2.7 |

0.3 |

3.1 |

1.4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

OAKLAND COUNTY |

|||||

|

Oakland County: ALL |

83.5 |

10.1 |

0.2 |

4.0 |

2.2 |

|

Whiteford township |

94.5 |

1.9 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

2.5 |

|

Addison township |

95.7 |

0.9 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

|

Auburn Hills city |

73.5 |

13.1 |

0.3 |

6.3 |

4.5 |

|

Berkley city |

95.2 |

0.7 |

0.2 |

1.0 |

1.3 |

|

Birmingham city |

95.3 |

0.9 |

0.1 |

1.5 |

1.2 |

|

Bloomfield township |

86.6 |

4.3 |

0.1 |

6.5 |

1.4 |

|

Bloomfield Hills city |

89.8 |

1.6 |

0.1 |

6.6 |

1.1 |

|

Brandon township |

96.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

1.6 |

|

Clawson city |

95.2 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

1.1 |

|

Commerce township |

95.9 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

1.3 |

1.2 |

|

Farmington city |

84.8 |

2.7 |

0.2 |

10.1 |

1.2 |

|

Farmington Hills city |

81.9 |

6.9 |

0.2 |

7.5 |

1.5 |

|

Ferndale city |

90.3 |

3.4 |

0.5 |

1.3 |

1.8 |

|

Groveland township |

95.5 |

0.8 |

0.3 |

0.5 |

1.7 |

|

Hazel Park city |

90.4 |

1.6 |

0.8 |

1.8 |

2.1 |

|

Highland township |

96.5 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

1.3 |

|

Holly township |

92.8 |

2.1 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

2.9 |

|

Huntington Woods city |

96.3 |

0.7 |

0.0 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

|

Independence township |

94.2 |

0.8 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

2.5 |

|

Keego Harbor city |

91.2 |

0.6 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

4.4 |

|

Lake Angelus city |

95.1 |

0.9 |

0.0 |

2.8 |

1.2 |

|

Lathrup Village city |

46.3 |

49.7 |

0.1 |

0.6 |

0.9 |

|

Lyon township |

96.1 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

1.5 |

|

Madison Heights city |

88.5 |

1.8 |

0.4 |

5.0 |

1.6 |

|

Milford township |

96.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

1.2 |

|

Northville city |

94.5 |

0.4 |

0.1 |

2.6 |

1.6 |

|

Novi city |

86.1 |

1.9 |

0.2 |

8.7 |

1.8 |

|

Novi township |

94.8 |

0.0 |

0.5 |

3.6 |

0.0 |

|

Oakland charter township |

93.3 |

2.0 |

0.1 |

2.6 |

1.2 |

|

Oak Park city |

46.4 |

45.7 |

0.2 |

2.2 |

1.3 |

|

Orchard Lake Village city |

91.2 |

3.8 |

0.1 |

2.6 |

0.9 |

|

Orion township |

93.7 |

1.2 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

2.6 |

|

Oxford charter township |

95.5 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

0.5 |

2.2 |

|

Pleasant Ridge city |

95.3 |

0.8 |

0.4 |

0.9 |

1.8 |

|

Pontiac city |

34.5 |

47.4 |

0.4 |

2.4 |

12.8 |

|

Rochester city |

91.1 |

2.2 |

0.2 |

3.7 |

1.7 |

|

Rochester Hills city |

87.1 |

2.4 |

0.2 |

6.8 |

2.3 |

|

Rose township |

95.5 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

2.2 |

|

Royal Oak city |

93.9 |

1.5 |

0.2 |

1.6 |

1.3 |

|

Royal Oak charter township |

22.6 |

71.1 |

0.2 |

1.2 |

1.2 |

|

Southfield city |

38.3 |

54.0 |

0.2 |

3.1 |

1.2 |

|

Southfield township |

91.5 |

3.6 |

0.1 |

2.2 |

1.2 |

|

South Lyon city |

95.6 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

1.1 |

1.6 |

|

Springfield township |

95.2 |

1.0 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

2.0 |

|

Sylvan Lake city |

94.5 |

1.1 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

1.1 |

|

Troy city |

81.3 |

2.1 |

0.1 |

13.3 |

1.5 |

|

Village of Clarkston city |

96.3 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

0.5 |

1.0 |

|

Walled Lake city |

94.3 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

|

Waterford township |

90.3 |

2.8 |

0.3 |

1.3 |

3.9 |

|

West Bloomfield township |

83.2 |

5.1 |

0.1 |

7.8 |

1.4 |

|

White Lake township |

95.4 |

0.8 |

0.4 |

0.6 |

1.8 |

|

WAYNE COUNTY |

|||||

|

Wayne County: ALL |

53.0 |

41.6 |

0.3 |

1.6 |

3.5 |

|

Allen Park city |

92.5 |

0.7 |

0.3 |

0.8 |

4.7 |

|

Belleville city |

86.3 |

7.9 |

0.3 |

1.1 |

2.5 |

|

Brownstown township |

86.6 |

3.8 |

0.4 |

3.8 |

3.6 |

|

Canton township |

82.3 |

4.5 |

0.3 |

8.7 |

2.3 |

|

Dearborn city |

84.8 |

1.3 |

0.2 |

1.5 |

3.0 |

|

Dearborn Heights city |

89.3 |

2.1 |

0.3 |

2.2 |

3.4 |

|

Detroit city |

10.5 |

81.2 |

0.3 |

1.0 |

5.0 |

|

Ecorse city |

47.3 |

40.4 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

8.9 |

|

Flat Rock city |

93.4 |

1.4 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

2.7 |

|

Garden City city |

94.6 |

1.1 |

0.4 |

0.7 |

2.0 |

|

Gibraltar city |

95.6 |

0.5 |

0.3 |

0.4 |

1.8 |

|

Grosse Ile township |

94.0 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

2.7 |

1.6 |

|

Grosse Pointe city |

96.1 |

0.8 |

0.1 |

1.1 |

1.5 |

|

Grosse Pointe township |

92.5 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

4.0 |

1.8 |

|

Grosse Pointe Farms city |

96.6 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

1.1 |

1.1 |

|

Grosse Pointe Park city |

91.2 |

2.9 |

0.3 |

1.8 |

1.7 |

|

Grosse Pointe Woods city |

95.5 |

0.6 |

0.1 |

2.1 |

1.0 |

|

Hamtramck city |

60.4 |

14.9 |

0.4 |

10.4 |

1.3 |

|

Harper Woods city |

84.9 |

10.2 |

0.3 |

1.7 |

1.6 |

|

Highland Park city |

4.0 |

93.1 |

0.2 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

|

Huron charter township |

94.3 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

2.5 |

|

Inkster city |

24.5 |

67.3 |

0.4 |

3.4 |

1.6 |

|

Lincoln Park city |

89.2 |

2.0 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

6.4 |

|

Livonia city |

94.1 |

0.9 |

0.2 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

|

Melvindale city |

81.7 |

5.2 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

8.9 |

|

Northville city |

95.8 |

0.3 |

0.1 |

1.2 |

1.7 |

|

Northville township |

88.1 |

4.3 |

0.2 |

4.3 |

1.8 |

|

Plymouth city |

95.5 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

1.1 |

1.3 |

|

Plymouth township |

91.2 |

2.9 |

0.3 |

2.7 |

1.6 |

|

Redford township |

86.7 |

8.5 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

2.0 |

|

River Rouge city |

49.9 |

41.8 |

0.6 |

0.2 |

5.0 |

|

Riverview city |

92.1 |

2.1 |

0.4 |

1.9 |

2.5 |

|

Rockwood city |

93.9 |

0.6 |

1.0 |

0.6 |

2.5 |

|

Romulus city |

64.3 |

29.8 |

0.5 |

0.7 |

2.0 |

|

Southgate city |

90.9 |

2.1 |

0.4 |

1.7 |

4.0 |

|

Sumpter township |

83.5 |

12.3 |

0.5 |

0.2 |

1.8 |

|

Taylor city |

84.0 |

8.7 |

0.6 |

1.6 |

3.2 |

|

Trenton city |

95.4 |

0.4 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

2.0 |

|

Van Buren township |

81.2 |

12.0 |

0.5 |

1.9 |

2.2 |

|

Wayne city |

83.0 |

11.3 |

0.6 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

|

Westland city |

85.6 |

6.7 |

0.4 |

2.8 |

2.5 |

|

Woodhaven city |

90.8 |

2.3 |

0.5 |

1.6 |

3.5 |

|

Wyandotte city |

94.3 |

0.5 |

0.4 |

0.3 |

2.9 |

|

Ypsilanti township |

66.1 |

25.3 |

0.5 |

2.0 |

2.8 |

Northern Michigan Shanty Creek/ Schuss Mountain Rental For Ski and Golf

Education Articles by Donna Gundle-Krieg

Blitzkriegpublishing home page